Christine Naswa, a 40-year-old roadside vendor and mother of five, stood by one of Nairobi’s busiest roads hawking sliced ginger. The pungent scent of her goods mixed with the fumes of passing buses as she shared her frustrations.

“The economy is very poor right now. There is no money in Kenya,” she said. “I can’t even feed my children. The cost of living is too high, and my profits are low. Some days, I earn nothing at all.”

Her story echoes that of many Kenyans struggling to stay afloat amid rising costs and dwindling opportunities. Though Kenya is considered an economic bright spot in East Africa, it faces deep-rooted challenges that have left millions behind.

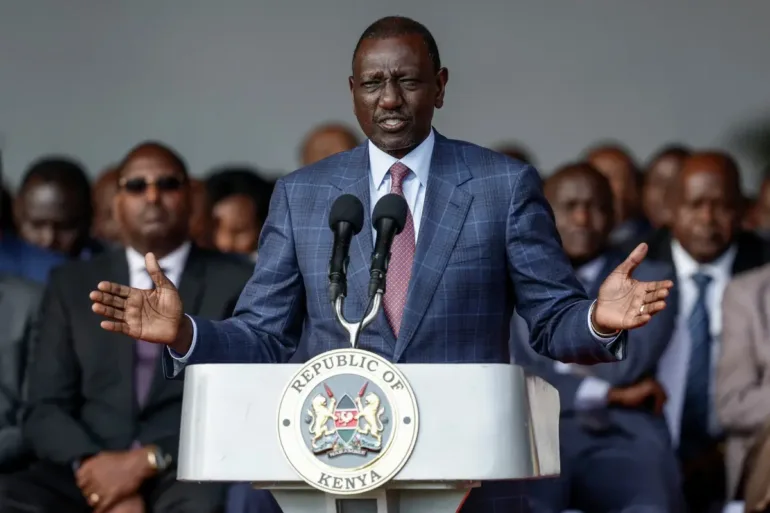

Around 40 percent of the population lives in poverty, with citizens increasingly disillusioned by a sluggish job market, rampant corruption, and a mounting tax burden. That frustration erupted in deadly protests in June last year, following the introduction of new taxes under President William Ruto’s finance bill.

Although some of the tax measures were later rolled back, many Kenyans say they feel more squeezed than ever.

“This year has been the toughest in our 36 years of business,” said a shopkeeper in Nairobi’s commercial district. Afraid to be named after his store was looted during the protests, he added:

“As soon as the new government came in, they started raising taxes. But we’ve seen no benefits.”

Kenya’s economy is diverse, with strong agriculture, services, and tourism sectors. But ascending to true middle-income status requires significant investment—something hampered by the country’s heavy debt load. Kenya now spends more on interest payments to foreign lenders than on health and education combined.

Despite that, Kenyans are growing increasingly resistant to further tax hikes, especially as only a small fraction of the workforce—less than 20 percent—is employed in the formal sector and bears the brunt of the tax burden.

“We’re at the limit of how much tax Kenyans are willing to bear,” said Kwame Owino, CEO of the Institute for Economic Affairs, a Nairobi-based think tank. “The idea that you can raise taxes to cover government inefficiencies and debts that many people believe weren’t used wisely—that idea is gone.”

The government is set to present a new budget to Parliament on Thursday, cautiously avoiding new direct taxes that could trigger fresh unrest.

President Ruto, who came to power in 2022 promising economic relief for ordinary citizens, is now facing mounting criticism for what many see as a betrayal of that promise.

“There’s a huge amount of distrust and disillusionment with Ruto’s administration,” said Patricia Rodrigues, an analyst at global consultancy Control Risks. “He promised a better life for ordinary Kenyans but instead increased taxes—and that was felt as a deep betrayal.”

While international bodies like the IMF urge Kenya to raise more revenue to meet the needs of its 55 million citizens, many believe that tackling corruption is the more urgent solution.

“Corruption is very deeply entrenched,” Rodrigues noted.

With the next general elections scheduled for 2027, some are already hoping for change. But not everyone is optimistic.

“Kenyans will always elect thieves,” the Nairobi shopkeeper said, shaking his head.

AFP